John the Scullion and ‘Multi-career women’

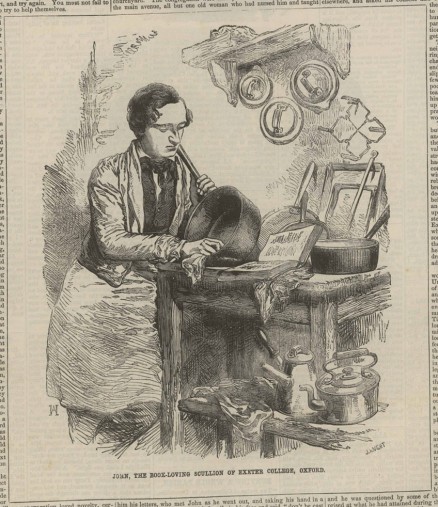

The British Workman encourages ambition in the face of adversity in many tales. One such is the story of ‘Disappointments; or John the Scullion’. This tale of determination focuses on ideas about ambition and achievement. Christian values underpin this personal determination, not just in content, but in ideas of destiny and God’s will. John wants to become parish clerk but the congregation does not vote for him. As a result, he endeavours to find work elsewhere. With ambitions of becoming a scholar, despite his large family and limited access to education, he goes alone to Oxford, and as a scullion in Exeter College, educates himself in any way he can.

In relation to work there is a huge emphasis on his character. John is frequently described as both honest and diligent. It is the latter that gets him noticed so that eventually he was questioned by some of the men in authority, who were surprised at what he had attained during the few intervals of his daily labour. They respected his diligence, and he was admitted as a sizar (poor student, or on the foundation) of Exeter College, and then, all his difficulties being over as to the means of attaining knowledge, he studied hard, and soon was among the most successful of college students. He was still very poor, for he had none to help him, he knew the poor parents he had left could not assist their son to become a scholar; but soon he was able to earn something by teaching students less advanced and less diligent than himself, and by slow but sure degrees his difficulties vanished, and in time, being as pious as he was industrious, studied for the church, was ordained, and became the ornament of the college that he had entered a friendless boy, and served as a scullion.

John establishes himself as a respected and prestigious scholar, and when he returns to his village he summarises the moral of the story; “and merits to be remembered by all who in early life are tried by disappointments, “If I,” said Dr. Prideaux, “had been parish clerk of Ugborough, I should never have been Bishop of Worcester.”. John gains status and identity through being ambitious but working hard, demonstrating how the British Workman promotes the ‘honest’ worker ‑ as long as that honesty is tied in with religious sentiments.

Even if the religious element has now disappeared, work-related articles aimed at the millennial continue to encourage ambition and preserve the notion that simple determination and hard work achieve success. The British Workman exploits literary exemplars of the honest hard working man and husband in the same way that current media idealise the “waitress to wealthy” tale. Feature films such as The Social Network and Steve Jobs demonstrate the collective interest in understanding how individuals achieved success. The increasing discussion on how we relate to role models sheds light on the significance of how we form our identity in the world of work and what motivates us. The popularity of literature that aims to motivate those disheartened in their work through explaining sentiments like ‘Why It’s So Important To Have Inspiring Mentors And Role Models’ demonstrates how integral it is to establish work goals and aspirations to shape our daily attitudes towards work.

The British Workman used royalty as an interesting choice of a role model for the working man. Utilising the news of the Death of the Prince Consort in 1862 to announce his status as not only a “Friend of the Sons of Toil” but to admire his work ethic as “an example for the lowliest, for the manifestation of those qualities of industry, ingenuity, promptitude, and benevolence, without which no working man can really make his life useful to himself or others.”.

The current press can be similarly accused of utilising unrealistic role models. In the same way that the Prince Consort does not relate to the experience of normal working men, the fantasy of the ‘The New Generation Of Multi-Career Women’ creates unrealistic expectations. Rather than providing an example to aspire to, these portraits of entirely flawless women are un-relatable figureheads of a system that continues to demean women.

With very little representation of the ‘in-between’, young working people may feel disenchanted with their own progress when in reality success is not always instant is not straightforward. Although the intent may be to inspire, these accounts of “modern day Renaissance women” do not provide the full scope and nuances of their everyday experience. Despite the way they are portrayed and the obstacles they have overcome, it is unlikely that these women feel like faultless working superheroes themselves. Sometimes they may be late, sometimes they might have a slow day, and I imagine some days they have off.

Read next: The Millennial in the Media: “Buy Your Own House”

VT